Speaking notes for Wincott Lecture ‘Can Multilateralism survive?’, 6 November 2018

This version: November 2018

This lecture is downloadable in pdf format here.

I don’t know what’s more humbling:

- To deliver this lecture after so many illustrious colleagues, some of whom are kind enough to be here today..

- Or for an economist to dare discussing the future of multilateralism in the temple of international relations..

- Or to have been assigned to speak on multilateralism precisely on the day of the Mid-term elections.

In fact I should not blame anyone about the topic, because I chose it.

And I chose it because a major battle is being waged that ranges from trade to finance, climate, the internet and many other fields.

It’s a battle about the organizing principles of international economic relations, whose outcome will be determinant for global prosperity, the preservation of global commons, and peace.

The last time such a battle took place was three quarters of a century ago at the time of the Atlantic charter, the Bretton Woods negotiations, and the failed attempt to create what was then called an International trade organisation.

The immediate reason why we are having this debate is, evidently, the stance of the Trump administration. What a difference a decade can make, from the G20 statement of 2009 to the pronouncements of the representatives of the US government!

Britain and the EU are firmly on the side of an international economic relations regime that prevents beggar-thy-neighbour behaviour, ensures equality of rights between nations, and cares about global public goods – what we loosely call multilateralism.

Rightly so: in an increasingly interdependent world, global public goods cannot be left unattended. Climate preservation, biodiversity, financial stability and internet security will not emerge from market interaction or the uncoordinated initiatives of national governments. Nor will they be engineered by a benevolent hegemon.

But the champions of multilateralism would be wrong not to acknowledge that the problem they are facing is not just the Trump administration.

Problems in fact started earlier:

- US grievances against the weakness of trade-related disciplines at the WTO did not start with the Trump presidency;

- Asian grievances against the IMF did not start with it either;

- And finally, popular grievances against financial liberalization did not start with it.

Problems also run deeper:

- Deep integration challenges and disrupts the traditional Westphalian model of international relations;

- China claims that global rules were written by incumbent powers;

- We are witnessing a major, nearly universal rise in the demand for national sovereignty.

In a sovereignty-conscious, heterogenous, multipolar, market-driven world, the simple deepening and broadening of the late 20th century order is not a realistic programme. It is likely to be a losing proposition.

So those of us who oppose the transactional approach to international economic relations and stand for multilateralism should start from a clear view of the problems multilateralism is facing and come up with a precise solution set they could rely on to address these problems.

What I intend to do in this lecture

1. A look back

It is hard to dispute that a step change in the intensity and nature of international economic integration has taken place over the last three decades. We call it globalization – a term that entered our vocabulary in the early 1990s

It encompasses five different dimensions:

- The integration of formerly communist countries, especially China, into the global economy;

- Knowledge flows and what Richard Baldwin called the « second unbundling »;

- Financial account liberalisation and its consequences for the transmission of financial shocks;

- The emergence of a new commodity made up of data;

- The rise of concerns over global commons such as climate and biodiversity.

It is in the 1990s that these transformations took shape. Not by accident, the 1990s also witnessed an intense reflection on the organising principles of this new global economy. And a strategy was devised to cope with it, which essentially consisted in strengthening and completing the institutional architecture of the post-war economic system.

Let me be clear. It would be exaggerated to speak of a full masterplan. But the spirit of the times was certainly that there would be, on the one hand, liberalisation and a broadening of the scope of the market and, on the other hand, the building of a strong policy architecture.

The WTO was indeed created in 1995, and plans were made to:

- Create a world competition system hosted by the WTO;

- Negotiate a multilateral agreement on investment;

- Give the IMF formal competence over the financial account;

- Cooperate on financial stability issues – initially within the Financial Stability “Forum”;

- Agree on a binding regime for climate change mitigation – the Kyoto protocol.

So it looked like world economic relations would be structured by a 7-pillar institutional architecture made up of hard institutions. That is, universal, treaty-based institutions equipped with resources, instruments or coercion powers.

Much of this vision did not materialise. And setbacks took place much before Trump

- An International competition system was considered 1995 by the EU, then abandoned;

- The MAI negotiations collapsed in 1998;

- The Extension of the IMF mandate discussed 1997, then abandoned;

- The FSB was hailed in 2009 as a « fourth pillar » of the global architecture, but has no power;

- The Kyoto protocol signed 1997 was de facto abandoned after the US pulled out in 2001.

The outcome is quite different from the vision.

Furthermore, if we look now as the performance of the existing institutions, the least we can say is that it has not fulfilled the promises made in the 1990s.

- The WTO was created in 1994, but it has not given rise to any new multilateral momentum. Rather, what we have witnessed is a burgeoning of regional agreements;

- Turning to the IMF, it has also failed to play the central role it was supposed to play. In spite of the decision to increase its resources taken in 2009 at the London summit, its role in the global financial architecture has diminished drastically. As the recent Tharman report pointed out, it is by now only a component of the Global Financial Safety Nets, alongside national reserves, bilateral swap lines and regional financial arrangements.

So it is fair to say that the strategic vision of the 1990s has by and large not materialised. The surge in interdependence resulting from liberalisation, technology and the growing importance of global commons has not been accompanied by a parallel strengthening of the institutional architecture of global governance.

2. The roots of the problem

I do not want to spend too much time discussing why the global governance programme failed to materialise. It would take long because the reasons are partly economic, partly political, and partly geopolitical.

Let me only mention three factors that are important from the perspective I am developing here.

Concentration

The first is the extreme concentration of economic weight in today’s global economy. The WTO has 164 members, the IMF 189 and the UN 193, but for most practical purposes, countries that really matter are at most 10% of this membership. This is illustrated by the distribution of global GDP or by a simple indicator such as the share of the top 10 countries in world total.

Such data illustrate what could be called the “WTO curse”: the paralysis that threatens universal institutions.

This especially applies to those, like the WTO, where decision by consensus is the rule.

Those, like in the Bretton Woods institutions, where votes are weighted and decisions are taken by qualified majority, are better equipped to avoid paralysis, but qualified majority voting is something the global community was not ready to consider in the 1990s and is even less ready to consider today. So the sheer number of participating countries – or entities is by itself a major impediment to the implementation of the global governance agenda.

This much more numerous global community is also much more diverse in terms of development. In 1944 the poorest of the countries participating in the Bretton conference was probably Haiti, whose GDP per capita was a tenth of that of the US. Today, Haiti’s GDP per capita is less than one-fourtieth of that of the US.

Development heterogeneity is evidently a major issue in an international system whose founding principle is the equality of rights among nations. It is fair to recognise that it has not been tackled adequately.

- First, the “developing country” status has become as much a political as an an economic characterisation – if not more: two-thirds of the WTO members, including China, are still categorised as « developing » – but there is no official list of them.

- Second, internal heterogeneity within countries that combine world-class clusters of economic performance and pockets of backwardness has grown but is not addressed effectively.

Networks

The second reason is the growing disconnect between the post-war global governance regime and actual shape of interdependence within today’s global economy.

We have been used of thinking of interdependence in terms of flows of goods and factors in and out individual economies. In this sort of representation economies are like islands connected by ship routes. It is still predominant in a large part of the public and it provides the model behind the actions of the Trump administration. But it is increasingly at odds with reality:

- Global Value Chains have transformed global trade, blurring the distinction between sectoral importers and exporters that underpins the organisation of trade negotiations;

- Financial globalisation has made net savings flows – current account balances – less significant in the transmission of shocks than gross financing flows and gross stocks of external assets and liabilities;

- The internet serves as a global infrastructure for both domestic and international transactions, without any distinction being made between them – my email to my wife may be travelling across borders;

- Finally, interdependence through climate change or the degradation of biodiversity is taking place without any transaction happening between islands.

So we may still be counting the ships entering and leaving the islands’ harbours, but this accounting is telling us less and less.

Research is gradually coming up with better models of interdependence. Yet we are still a long way from having elaborated an adequate representation – and from being able to draw from it the proper governance consequences.

Multipolarity

The third reason is the increasingly multipolar character of the global economy.

In 1945, according to Angus Maddison, the share of the US in global GDP measured in PPP terms was 27%. The next country was the UK with a 6.5% share. Such a disproportion was exceptional by historical standards: in 1870 for example, Queen Victoria’s empire represented 22% of world GDP but China was a close second with 17% – though admittedly it was also a remote second.

Today’s situation is completely different: according to the IMF (whose data differ from those of Maddison), China is first with almost 19%, followed by the US with 15% – roughly the same numbers as in 1913, when the US overtook the British empire as the world economy’s powerhouse. But there are two major differences:

- First, China is far from being dominant in a number of essential fields where the US remains unrivalled – science, finance and the military, just to name the three main ones;

- Second, we also have the EU – also 15% if we are still counting Britain in it – and then India with almost 8%, a share that is rapidly rising.

What we are witnessing is not only the rise of the emerging power and the relative decline of the incumbent, but the emergence of a truly multipolar global economy.

The problem is that from an economic perspective, there is little we can pretend we know about the functioning of a multipolar system.

We have a reasonably good understanding of the functioning of a hegemonic system – here, economists and political scientists converge to describe it as an implicit contract whereby the hegemon benefits from rents – especially, the famous “exorbitant privilege” arising to the issuer of the international currency – and takes on exorbitant duties – especially, the fiscal risk involved in providing emergency liquidity to the overseas users of its currency.

And we also have a reasonably good hunch of why the incumbent power may decide to change the rules of the game if it perceives that the exorbitant duties exceed the exorbitant privilege, or simply if its time preference is such that it prefers to convert long-term benefits into short-term rents.

But we do not know much about how a truly multipolar system should work. International negotiations can define principles and rules that apply to all participants in normal times. They can hardly determine how discretionary power arising from economic centrality will be exercised in crisis times. It can hardly decide who should be the guarantor of the system, which risks this or these countries should be ready to take and what costs they might be willing to incur to preserve the integrity of that system.

This is certainly a lesson we have learned from the euro crisis, even though the eurozone is equipped with mechanisms for qualified majority decision.

And even agreement on principles and rules for normal times may be difficult to reach if the leader of the largest economy expresses scepticism vis-à-vis the global order, as president Xi Jinping has done.

It would not be fair to say that international organisations have remained immobile in front of these tectonic changes. For example, the WTO has developed an analysis of trade in value added and the IMF has addressed financial spillovers arising from gross cross-border flows. And the BIS has developed research into a deeper understanding of financial globalisation.

It remains true, however, that what emerges from analysis is the obsolescence of the global governance system. Since the mid-1990s,

- The institutional architecture of globalisation has not been fundamentally reformed to address emerging challenges;

- Reforming existing institutions has been painful and slow.

- More fundamentally, the basic structure of the global governance set-up has remained too dependent on the “islands” representation.

3. Alternative arrangements for collective action

If the conclusion is that there are deep reasons to doubt that the proponents of multilateralism can set themselves the goal of completing the late-20th century global governance agenda, what is the alternative?

Emerging arrangements

A good starting point for answering this question is to assess what is actually happening. And what is happening is that the vacuum left by non-existing institutions is being filled, at least partially.

We have witnessed over the last decades the rather disorderly emergence of a variety of arrangements – sometimes outside the formal global governance system, sometimes within it or at least in connection with it. What has emerged is:

- Self-insurance (through the accumulation of FX reserves)

- Bilateral agreements (in development finance, financial safety nets)

- Regional arrangements (in trade, development, financial safety nets)

- Coalitions of the willing (in trade)

- Voluntary cooperation between independent authorities (in competition)

- Global pledge and review agreements (in climate, banking regulation)

- Multi-stakeholder fora (for the internet, also climate change mitigation)

These arrangements have introduced a number of innovations.

- Some have relaxed the universal membership constraint to build clubs involving the most relevant players.

- Some have got rid of the Westphalian constraint to include non-state players such as subnational governments, private companies or non-profit associations.

- Some have eliminated the legal constraint that required cooperation to be rooted in international treaties.

- Some have ignored the institutional constraint, building informal coordination procedures amongst key players.

- And some have put aside the principle that international cooperation be based on specified obligations to put the emphasis on nudge and incentives arising from reputational concerns, opinion pressure or market pressure.

Assessing the arrangements

Can ad-hoc, sometimes loose arrangements substitute the would-be pillars of the governance architecture? Can they be effective in addressing global governance challenges? Academics and seasoned practitioners of international organisations are often critical of such arrangements – at least they find them perplexing. They point out that universal rules and institutions have been designed for good reasons:

- because they protect the weaker countries – that’s for example the role of the WTO’s Most Favoured Nation provision;

- because, as it is the case with the IMF’s Article 4, they ensure discipline and prevent predatory, beggar-thy-neighbour behaviour;

- because they avoid free-riding;

- and because truly multilateral cooperation is cost-effective – again, the comparison between self-insurance through reserve accumulation and multilateral insurance through participation in the IMF is a case in point.

Critics are right to point out that faith in ad-hoc arrangements can be a fig leaf for endorsing ineffectiveness. Ideas put forward by practitioners or international relation scholars are often suggestive, but fail to convince that such issues are dealt with systematically enough.

To take only two examples, the “sovereign obligation” concept put forward by Richard Haass to highlight the duties of sovereign states to their neighbours and partners and the “creative coalition” concept proposed by the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations led by Pascal Lamy (Oxford Martin Commission, 2013), belong to two opposite traditions but share the absence of a systematic treatment of participation incentives and enforcement challenges.

The same issue arises in the Westphalian world of Haass and the post-Westphalian world of Lamy: how do participants overcome the collective-action problem? Neither approach offers a compelling solution to the participation and enforcement challenges involved in any joint endeavour.

The danger of simple models

By the same token, however, we should beware of analysing reality through the lenses of overly simplified models that may yield forceful results but may misrepresent the true nature of the interactions at work. Obstacles to successful cooperation are pervasive, but not systematically as decisive as suggested by such oversimplified models.

Especially, the frequent reliance on a prisoners’ dilemma structure to represent the nature of the underlying international game can be misleading.

Let me take a few examples to clarify this point.

If envisaged in a static framework without endogenous technical progress, climate change mitigation provides an example of a true prisoners’ dilemma game. In a multiple-countries setting, each of those faces a strong incentive to free-ride and leave to the others the burden of investing in the reduction of greenhouse gases emissions. As demonstrated by William Nordhaus (2015), one of this year’s Nobel prize recipients, voluntary climate coalitions are inherently instable. So there is a need for a coercion or a sanction system that ensures that externalities are internalised. This is a case where the simplified model applies.

But assume now, as in the model of Daron Acemoglu, Philippe Aghion and co-authors, that instead of working with a given set of technologies, climate change mitigation relies on endogenously developing clean technologies that initially do not match the productivity of the dirty ones but have the potential to develop and reach or exceed that level. This transforms the game and the purpose of public policy which may take as a goal to foster the development of clean technologies instead of the full internalisation of the climate change externality. What matters then is to reach a critical mass of private investments that will help put the economy on a different trajectory. Instead of a prisoners’ dilemma game, what we now have is an assurance game where incentives to cooperate are much stronger.

Take now financial stability. Here also there are strong cross-country spillovers, but a country’s financial stability depends first and foremost of its own policies and of the soundness of its own financial institutions. So each country’s authorities have an incentive to act – unless they believe that partners won’t act and that it is therefore pointless to incur the costs of limiting risk-taking at home if the global financial system is bound to collapse. What cooperation requires here is much less than compulsion or sanction – rather, enough transparency to create trust and convince each player that its efforts are not going to be frustrated.

Take finally the issuance of an international currency. Here, clearly, economies of scale as such that one, at most two countries will be providing the essential vehicle for global trade and finance. It is a bit like for disease control, a field where the US is providing to the rest of the world the information on diseases it collects and monitors.

An Ostrom-like programme

The upshot is that there are different types of interactions and different types of games which do not necessarily call for the same type of governance response. What is required to elicit trust is not the same as what is needed to prevent the free-rider curse.

This has significant implication for governance: we should neither trust whatever loose arrangements through which hard collective action problems are purportedly tackled, nor assume that nothing but a strong public organisation equipped with coercion powers can address the curse of free riding. We should be more modest, more empirical and endeavour to find out, at very granular level, which arrangements can solve which problem.

What I am saying here is in fact close to what Elinor Ostrom wrote about the variety of arrangements in place at grassroot level for managing local commons such as rivers, lakes or forests. Here research aim was to « dig below the immense diversity of regularized social interaction [..] to identify universal building blocks used in crafting such structured interactions ».

In a similar way, an agenda for devising arrangements conducive to global collective action should:

- Analyse critically arrangements in place to find out what is the underlying collective action problem they are providing a solution to;

- Determine which are the mechanisms through which this solution is being provided;

- Determine if they actually deliver results;

- Assess their robustness.

4. Lessons from emerging arrangements

So what does the empirical analysis of existing arrangements tell us? Here I am going to limit myself to a few fields and give a snapshot of the early results from an analysis undertaken within the framework of a project initiated jointly with George Papaconstantinou at the European University Institute. The project involves a review of existing arrangements in several sectors on the basis of the framework I have presented. Results at this stage are far from comprehensive but they are nevertheless informative.

Clubs and incentives

Three conclusions strongly emerge:

- The first is the predominance of variable-geometry, or club arrangements. Clubs are the name of the game in almost all fields but climate change mitigation, which by nature aims at universal reach. Clubs prosper because they are smaller, more flexible, better tailored to the needs of cooperation between the players who really matter. Most of these clubs are open-door groupings, to which new members can opt in at will or after a relatively light screening process – on the condition, obviously, that they commit to abide by the rules of the club;

- The second is the general reliance on incentive mechanisms. None of the emerging governance arrangement involves formal compulsion backed up by sanctions. The pledge and review template, whereby participating countries do not abide by mandatory rules but accept that their behaviour be monitored and reported, is visibly gaining traction;

- The third is that a number of arrangements deliberately involve non-government players. This is especially true of the Paris climate agreement whose architects regarded this involvement as a substitute for the lack of legally-grounded implementation mechanisms. But evidence of private involvement is strong in trade, banking regulation and obviously the governance the internet.

Mechanisms

The table below reviews the membership, institutional backing, mechanisms and effectiveness of arrangements in five key fields. Details are provided in the appendix.

Table: Summary governance arrangements in place in five fields

| Trade | Competition | GFSN | Banking | Climate | |

| Membership | Universal (WTO) + clubs | Club | Universal + clubs | Club | Universal |

| Institutional support | WTO | none | IMF | BCBS | IPCC |

| Interdependence structure | Multi-level clubs | Oligopoly | Hub and spoke | Oligopoly | Global common |

| Mechanisms | Rules-based agreements | Informal cooperation | Rules-based + discretionary decisions | Pledge and review | Pledge and review |

| Non-government involvement In governance | Significant | Quasi-judicial process | Limited | Significant | Significant |

| Effectiveness | Significant but relies on WTO principles | Remarkably effective so far | Yes but costly | Yes but risk of capture | Uncertain |

| Robustness | Significant | Vulnerable to changes in national legislations | Multi-level cooperation problematic | Vulnerable to disruption (non-banks, third countries) | Lack of effectiveness may threaten permanence |

Mechanisms

Clubs and the reliance on incentives are in fact mutually reinforcing. A strength of clubs is that enforcement of commonly agreed commitments is not dependent on legal provisions, the settlement of bilateral, disputes, or sanctions. A member that does not fulfil its commitments can simply be expelled, or at least, it can be signalled that it does not abide by the common rule.

This is for example the mechanism underlying banking regulation: standards are negotiated by all the members of the club, but each country is free to adopt, implement and enforce them. However, the member countries performance is reviewed on a quarterly basis by the Basel committee and the result of this evaluation is made available to market participants and the public. This has proved to be an effective mechanism to encourage the decentralised implementation of centrally-agreed provisions.

Universal institutions are instead more dependent on the existence of binding obligations and formal enforcement mechanisms. This is evidently a weakness of the COP21 climate mitigation agreement, which is both universal and non-binding. Commitments and delivery on commitments are being reviewed, but little can be done in case a member country does not deliver. In fact, there is no evidence that the Paris agreement will result in member countries putting forward ambitious enough agreements and delivering on them.

Overall, it is fair to say that these arrangements are relatively weak. Even when they look effective superficially, they may have their downsides. Banking regulation through a club mechanism is a good example. At one level it is effective, but at the cost of favouring regulatory capture and of being vulnerable to disruption coming from new participating countries or new type of (non-bank) agents.

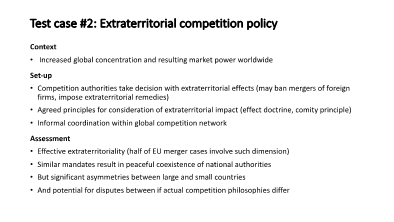

Another club, that formed by the competition authorities, also looks vulnerable. It is remarkably effective in that it has been able to address global competition problems on the sole basis of an organised coexistence between the main national authorities. But its effectiveness rests on a consensus between authorities whose mandate are similar and that enjoy a similar degree of autonomy vis-à-vis political authorities. This consensus may not last.

5. Policy implications

Let me finally move towards addressing policy implications of what I have developed. They fall short of providing a template for a renewed multilateralism but nevertheless provide guidance for thinking about such an agenda.

I would wish to offer five such conclusions.

First, and again, policymakers should accept that completing the post-war legal and institutional architecture is not the way forward anymore. I don’t need to dwell any further on this point.

Second, existing club-type, incentive-based soft global governance arrangements provide a wealth of experience to learn from but they should be assessed critically. It’s hard to find the right balance between complacency and scepticism, but I am afraid that’s what needs to be done.

This assessment requires hard work because, again, it can only be carried out at very granular level, on the basis of a precise reading of the interaction involved, the resulting game structure, and the nature of the collective action problem that is to be solved.

The problem policymakers are facing is that they are not very well equipped for this sort of assessment. There is a role for good policy research here, in that it could provide them with a toolkit for this sort of ex ante evaluation.

Third, a case can be made for anchoring clubs in universal principles. Such principles are needed to avoid letting clubs becoming exclusive and falling into an ad-hoc, possibly purely transactional approach. The template here is trade, where regional agreement, preferential agreements and plurilateral agreements are governed by general WTO provisions such as national treatment and the most-favoured nation clause. This also applies, in a less formal way, to international finance and the role regional financial safety nets.

This anchoring is a way to combine the flexibility of clubs with essential principles that underpin international economic relations.

Fourth, we should change the way we think about international institutions. They should not be regarded as sectoral empires for technocrats, but as poles of expertise able to devise solutions, support initiatives and provide monitoring.

Institutions are the global governance’s social capital. Such capital is scarce and as discussed already, the likelihood that new global institutions are going to see the light is low. So a case can be made for maximising the value existing institutions can deliver. This implies accepting the borders of their sectoral remit be soft rather than hard and this suggests that the focus in their governance should be less about their powers and resources and more about their analytical and organisational capabilities.

Fifth, we should think more systematically about the involvement of the private sector in governance arrangements. A governance system that does not rely on a strong legal basis and that cannot rely on sanctions is inevitably inclined towards involving stakeholders as a way to increase its effectiveness.

This has been the strategy explicitly followed for the Paris climate agreement, with some success. And there are numerous other examples, from sectoral regulations to the internet. There is nothing wrong about this approach, but it should not serve as an excuse for discharging of policy responsibility. The market can be part of the mechanism design, but the market won’t do the job.

Some institutions already provide examples of such a role: the IMF was not initially designed as an institution monitoring global capital markets, nor the OECD as an assessor of educational achievements.

In today’s world, multilateralism not require delegating competence to powerful global bodies, but it does require nimble institutions that are able to provide expertise, tell the truth, experiment and propose.

Let me close finally with the question I started from: can multilateralism survive? Only reality will tell us. But if it is to survive, it will be in a significantly different form than the one we inherited from the architects of the global economic regime. Its supporters would be well inspired to take notice and formulate an agenda for what could be called “parsimonious multilateralism”, or probably better, “critical multilateralism”: an approach that focuses on the essential and ensures that the best use is made of necessarily limited tools.

Appendix